Ferdi McDermott

When The Parting Hour appeared in May 1895, accompanied by a full-page illustration in The Pall Mall Magazine, it marked Olive Custance’s entry into public life. The poem was reprinted across Britain, the United States, and the colonies, appearing in newspapers from London to Sydney. Within weeks, her name was familiar to readers well beyond literary circles. Yet the sudden attention was the outcome of nearly ten years of steady work, reading, and correspondence.

Olive Eleanor Custance was born in London in 1874, the elder daughter of Colonel Frederick Custance of the 5th Lancers and Eleanor and Eleanor Custance (née Eleanor Constance Jolliffe). The family divided its life between the social world of St John’s Wood and the quiet of Weston, near Attleborough, Norfolk. Weston’s garden and fields gave her the imagery of her early poems: the recurring motifs of spring rain, lilac, and twilight that later appeared in Opals.

Her education was domestic. With her sister Cecil, she was taught by a Scottish governess, Tanie, who provided a balanced grounding in music, French, and moral discipline. Tanie’s calm authority and religious sensibility left a clear trace in Olive’s later poetry.

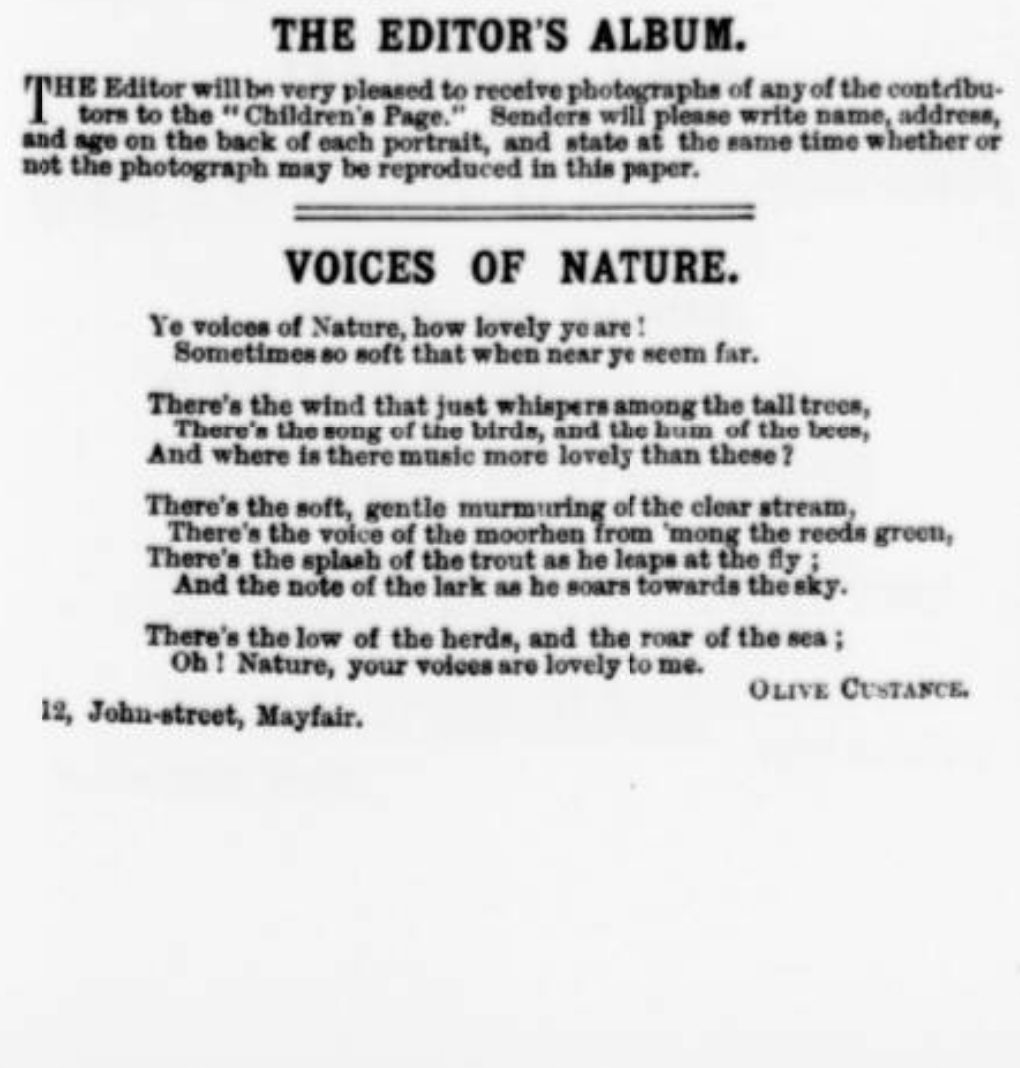

Encouraged by her mother, Olive began submitting poems to The Lady’s Pictorial in her early teens. Her first published work, Voices of Nature (1888), appeared with a brief editorial note praising her promise. This exchange began a routine of submission, comment, and revision. The editors’ advice was practical—“your writing has improved a little”—but their engagement provided her with a form of apprenticeship. The Lady’s Pictorial and The Gentlewoman offered a space where young women could learn the conventions of print culture, and Olive used it fully. Writing under her pseudonym “Wild Olive,” she gained confidence, learned editorial discipline, and began to see herself as a professional.

By the early 1890s she had travelled to France with family connections, improving her French and attending Mass regularly. Exposure to Catholic ritual and French literature deepened her sense of beauty as something sacred and disciplined rather than purely decorative. In her diary of 1895 she described Walter Pater’s Marius the Epicurean as a revelation, saying that it expressed her own soul in prose. It confirmed her belief that art and moral seriousness could coexist.

Returning to England, she moved in her mother’s social and artistic circles in Kensington and St John’s Wood. These contacts gave her access to editors and publishers, but she continued to rely on her own initiative and wrote furiously to newspapers seeking publication of her poems, and accepting any helpful advice she got back from Editors. Her father treated her literary interests with tolerant amusement, but her persistence was unmistakable.

Her chance came when The Pall Mall Magazine accepted The Parting Hour in 1895. The poem’s measured sentiment—“The sunset fades, and twilight grows apace, / The hour has come, my love, the parting hour”—and its accompanying illustration by J. Walter West perfectly suited the tastes of late-Victorian readers. Its success was immediate. The artwork featured on the Frontispiece. Remarkable for a girl of her age. Reprints appeared in newspapers across the English-speaking world, often with her name printed in bold. She was to become for a few years, one of the best-known young poets in Britain.

That success was not luck but the result of years of preparation. Through the discipline of the women’s press, she had developed technical skill, a sense of audience, and the confidence to present herself as a writer. Her upbringing, travel, and reading combined to form a distinctive voice: lyrical, restrained, and aware of beauty’s moral weight.

By the time her poem made her famous, Olive Custance was no longer an amateur. The years of practice behind her first success explain why she could step so easily into the literary world that awaited her. What looked like an effortless debut was the work of a decade spent learning her craft in private before her name reached print.

For the first time since he 1880s, we believe, here is Olive’s first ever published poem:

“Voices of Nature” – The Lady’s Pictorial, Saturday, 15 September 1888, p. 19

By Olive Custance (aged 14)

Ye voices of Nature, how lovely ye are!

Sometimes so soft that when near ye seem far.

There’s the wind that just whispers among the tall trees,

There’s the song of the birds, and the hum of the bees,

And where is there music more lovely than these?

There’s the soft, gentle murmuring of the clear stream,

There’s the voice of the moorhen from ’mong the reeds green,

There’s the splash of the trout as he leaps at the fly,

And the note of the lark as he soars towards the sky.

There’s the low of the herds, and the roar of the sea;

Oh! Nature, your voices are lovely to me.

References

- The Lady’s Pictorial (issues from 1888–1894), featuring early poems and correspondence, often under the pseudonym “Wild Olive.”

- The Gentlewoman (early 1890s), containing additional short verses and editorial comments.

- Custance, Olive. Diary entries, circa 1895 (Berg Collection, New York Public Library).

- The Pall Mall Magazine, May 1895: publication of The Parting Hour, with illustration by J. Walter West.

- King, Edwin, (ed.), The Inn of Dreams: Poems by Olive Custance, St. Austin Press, 2015.

- Adams, Jad. “Olive Custance: A Poet Crossing Boundaries,” English Literature in Transition, 1880–1920, vol. 61, no. 4 (2018), pp. 43–60.

- Wintermans, Caspar. Alfred Douglas: A Poet’s Life and His Finest Work, 2007.

- Hawkey, Nancy. Olive Custance Douglas: An Annotated Bibliography of Writings About Her, 1972.

- McDermott, Ferdi. “Olive Custance: The Poison Pen of a Fairy Prince,” The Fortnightly Review, 23 April 2020.