The brief encounter between Olive Custance and John Gray occupies a small but revealing place in the history of the 1890s. It shows not only the emotional openness of the young poetess but also the religious and aesthetic vocabulary she drew from her cultural milieu. Brocard Sewell’s In the Dorian Mode: A Life of John Gray, 1866–1934 (Padstow: Tabb House, 1983) remains the principal source for the episode, preserving the text of Olive’s diary and correspondence.

Sewell recounts that Olive, “a young society girl of aristocratic family,” met Gray “at a party” when she was about sixteen (c. 1890–91) and “fell in love with him at once.”1 “She must have been an extremely beautiful girl,” he adds, “and if only he had been attracted to her, her future life might have been happier.” Gray, ten years her senior, was courteous but unresponsive; nevertheless, he became for her “my ideal Poet.”

Her diary entries for 4 and 8 January 1896, quoted by Sewell, describe her joy in hearing from Gray and receiving Silverpoints:

“I had sent John Gray some of my poems, and the New Year brought a beautiful letter from him—and the photograph I so much desired and a book, Miracle Plays by K. Tynan Hinkson …”

“Then again next morning he came and brought me Silverpoints and was so kind and talked so beautifully—and looked so nice. He is my ideal Poet … and we were, I think, a happy little trio … But at last we all had to say goodbye—and he went home and sent me at once a lovely book and a charming little note.”

Two years earlier, at Christmas 1894, Olive had written from Weston, Norfolk, to a friend she calls “Lulu,” enclosing one of Gray’s privately printed Blue Calendars, little devotional booklets of verse. Her letter, quoted in full by Sewell, reveals both literary admiration and spiritual longing:

“Lulu, I send you a book and a song. For Christmas … A Poet—whom I once met as a child (I was about sixteen, and he was twenty-five)—wrote to me the other day and sent me his book—privately printed—of Carols on the life of the Christ Child. I think I may have spoken to you about him as he has been for a long while my Prince of Poets. There is not one who can sing like him—his poems are so precious and so pure … He has lived a strange full life and now he writes:

‘At a certain time one is apt to want to live for grace. Soon the better ideal comes—to live well and chance the grace. And is it not so with poetry? Have you come to the determination to write well at every risk—to put more fire into your work than anyone else could ever find out?’

Ever your loving WILD OLIVE.”

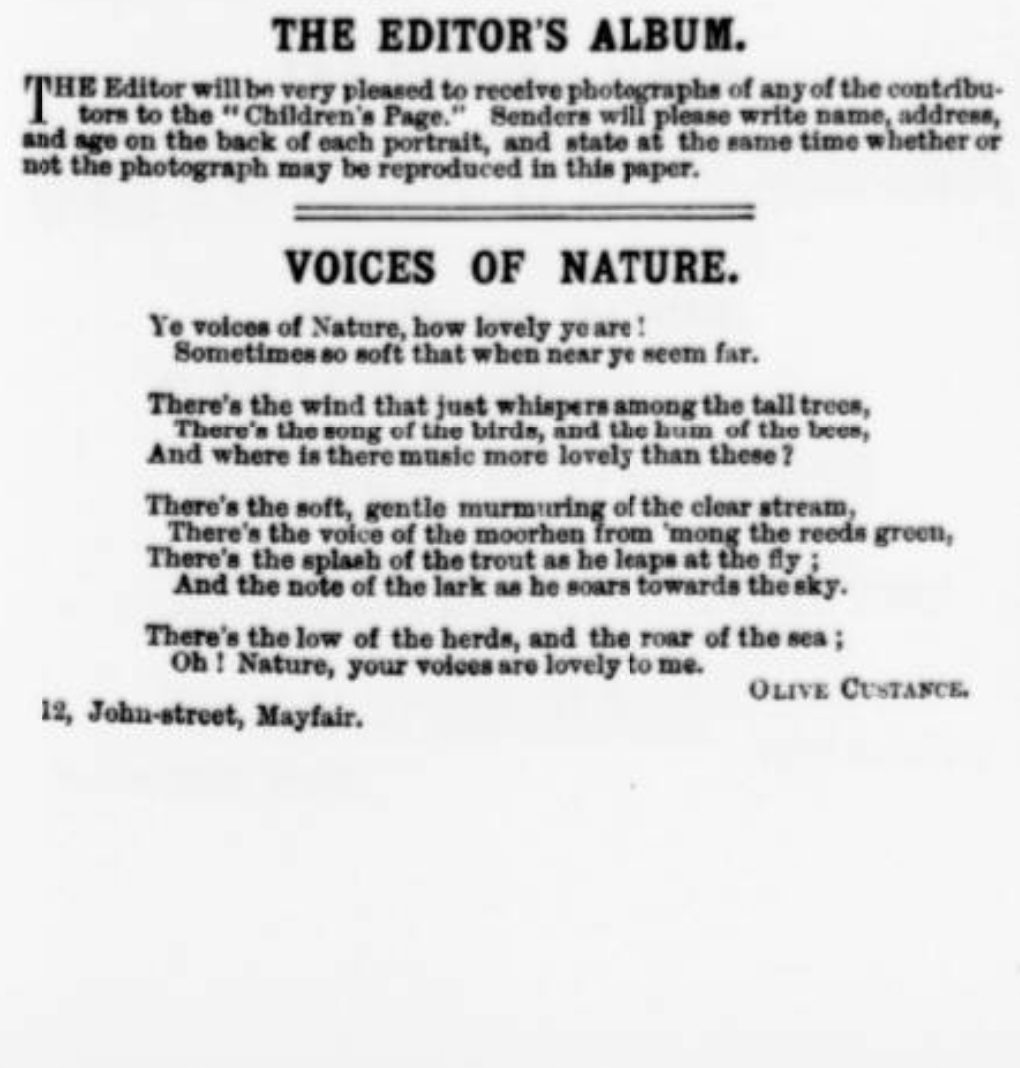

Sewell described this as “the earliest use of the name Wild Olive,” observing that it expressed “both her youthful piety and her continuing fascination with the man she still called ‘my Prince of Poets.’”4 Later evidence, however, shows that Olive had adopted the name six years earlier, in 1888, when she was only fourteen. Several brief verses and letters signed “Wild Olive” appeared that year in The Lady’s Pictorial (London), showing that she had already fashioned a poetic persona from the phrase before ever meeting Gray.5 The 1894 letter thus represents not the creation but the revival and re-baptism of the name in a devotional key.

The Ruskinian Origin of “Wild Olive”

The term “Wild Olive” itself is drawn from John Ruskin, who used it repeatedly as a moral emblem. In Unto This Last (1860) and again in Ariadne Florentina (1876) and The Queen of the Air (1869), Ruskin contrasts the “wild olive” — the untamed human will — with the cultivated olive of peace and divine order:

“The wild olive is the type of man’s own wild will and intellect; but the tree of peace, the true olive, is planted only by the waters of obedience.”

For readers of the 1880s his phrase had a clear allegorical resonance: nature awaiting cultivation by grace. By adopting Wild Olive as her pen name, Olive Custance combined a literary pun on her Christian name with a Ruskinian emblem of the soul’s conversion from natural vitality to spiritual fruitfulness. In her later reuse of the signature, after meeting Gray, it came to symbolise precisely what she admired in him: the reconciliation of beauty with sanctity, art with faith.

Poems from the Episode

Two poems survive from this period of devotion. The first, “Reminiscences,” printed in Rainbows (London: John Lane, 1902, p. 29), looks back upon the long-past meeting: “Just once we met, / It seems so long ago …”.6

The second, “To John Gray,” was never included in her collections but was printed by Sewell from a manuscript now lost. Written probably between Opals (1897) and Rainbows (1902), it distils the same emotion in a more formal sonnet:

We are not sundered for we never met.

We only passed each other in the throng;

You were indifferent … and I may forget

Your profound eyes, your heavy hair, your voice

So clear, yet deep and low with tenderness,

That lingered on my ears like a caress

And roused my heart to make a futile choice.

O Poet that clamoured unto God in song!

How should I lose you thus and lack regret?

When, in 1898, Gray resolved to enter the Scots College in Rome to prepare for the priesthood, “among those who understood and approved his decision were Olive Custance and Lady Currie.”7 Thus, even after his retreat from literary society, Olive continued to venerate him, seeing in his conversion the fulfilment of the ideal she had already expressed through her Ruskinian pseudonym — the wild olive grafted into the true tree of peace.

References

-

Brocard Sewell, In the Dorian Mode: A Life of John Gray, 1866–1934 (Padstow: Tabb House, 1983), p. 56.

↩︎ -

Ibid., p. 57.

↩︎ -

Ibid., p. 61.

↩︎ -

Ibid.

↩︎ -

See The Lady’s Pictorial (London), issues of 1888, where several short poems and letters by Olive Custance appear under the signature “Wild Olive.”

↩︎ -

Olive Custance, Rainbows (London: John Lane, 1902), p. 29.

↩︎ -

Sewell, In the Dorian Mode, p. 90.

↩︎